[1]

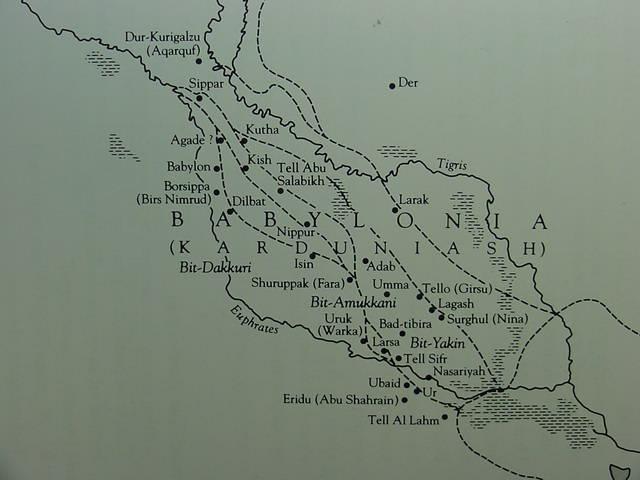

Urukagina, the leader of the Sumerian city-state of Girsu/Lagash, led a popular movement that resulted in the reform of the oppressive legal and governmental structure of Sumeria. The oppressive conditions in the city before the reforms is described in the new code preserved in cuneiform on tablets of the period: "From the borders of Ningirsu to the sea, there was the tax collector." During his reign (ca. 2350 B.C.) Urukagina implemented a sweeping set of laws that guaranteed the rights of property owners, reformed the civil administration, and instituted moral and social reforms. Urukagina banned both civil and ecclesiastical authorities from seizing land and goods for payment, eliminated most of the state tax collectors, and ended state involvement in matters such as divorce proceedings and perfume making. He even returned land and other property his predecessors had seized from the temple. He saw that reforms were enacted to eliminate the abuse of the judicial process to extract money from citizens and took great pains to ensure the public nature of legal proceedings.

[2]

As can be gathered from what has already been said about social and economic organization, written law played a large role in the Sumerian city. Beginning about 2700 B.C., we find actual deeds of sales, including sales of fields, houses, and slaves. From about 2350 B.C., during the reign of Urukagina of Lagash, we have one of the most precious and revealing documents in the history of man and his perennial and unrelenting struggle for freedom from tyranny and oppression. This document records a sweeping reform of a whole series of prevalent abuses, most of which could be traced to a ubiquitous and obnoxious bureaucracy consisting of the ruler and his palace coterie; at the same time it provides a grim and ominous picture of man's cruelty toward man on all levels—social, economic, political, and psychological. Reading between its lines, we also get a glimpse of a bitter struggle for power between the temple and the palace—the "church" and the "state"—with the citizens of Lagash taking the side of the temple. Finally, it is in this document that we find the word "freedom" used for the first time in man's recorded history; the word is amargi, which, as has recently been pointed out by Adam Falkenstein, means literally "return to the mother." However, we still do not know why this figure of speech came to be used for "freedom."

[3]

[4]

[5]

Le Louvre Museum | number AO 24414 | Foundation tablet | Dimensions 25.7*13.7*7.2 cm

En-metena E l. 9. 5. 5aA sixteen-line inscription found on foundation tablets and bricks records En-metena's construction of the E-mus temple.Translation:

iii 10 - iv 3) He cancelled obligations for Lagas, restored child to mother and mother to child.iv 4-5) He cancelled obligations regarding interest-bearing grain loans.iv 6 - v 3) At that time, En-metena built for Lugalemus, the E-mus ("House — Radiance [of the Land]") of Pa-tibira, his beloved temple, restoring it for him.v 4-8) He cancelled [obligations for the citizens of Uruk, Larsa, and Pa-tibira.v 9-11) He restored (the first) to the goddess Inanna's control in Uruk,vi 1-3) he restored (the second) to the god Utu's control in Larsa,vi 4-6) he restored (the third) t[o] the god Lugal-emus's control in the E-mus (in Pa-tibira).

[6]

Le roi En-metena (2404-2375) a régné sur la cité-état de Lagash. La tablette de pierre provient des fouilles effectuées à Tello, ancienne Girsu, située dans l'actuel Iraq. Elle était une pierre de fondation du grand temple de la ville de Bad-Tibira [l'E-mus de Pa-tibira]. Elle date d'environ 2400 av. J.C. Elle est actuellement conservée au Musée du Louvre, qui l'a acquise en 1971.

[7] !!

Pour la lecture des inscriptions, la numérotation des cartouches par Frayne se suit de bas en haut et de gauche à droite.

[8]

...

Sur les images dorées

Sur les armes des guerriers

Sur la couronne des rois

J’écris ton nom

...

Et par le pouvoir d’un mot

Je recommence ma vie

Je suis né pour te connaître

Pour te nommer

Liberté

(Paul Eluard, 1942)

Références:

[1] (S.N. Kramer, 1897 – 1990 ; From the Tablets of Sumer: Twenty-Five Firsts in Man's Recorded History, 1956)

[2] (S.N. Kramer, 1897 – 1990 ; The Sumerians. Their History, Culture and Character, 1963)

[4] (J.S. Bergsma ; The Jubilee from Leviticus to Qumran: A History of Interpretation, Volume 115, 2007)

[6] Références complètes de la tablette de pierre : Musée du Louvre

[7] Source des images de la tablette et sa localisation dans le musée, pour conclure ces 15 heures de recherche dans notre mémoire commune.

[8] (Paul Eluard, 1895 - 1952 ; Poésies et vérités, 1942)

[8] (Paul Eluard, 1895 - 1952 ; Poésies et vérités, 1942)